Adam Smith in Beijing: Harvey, Patnaik and devalorization

|

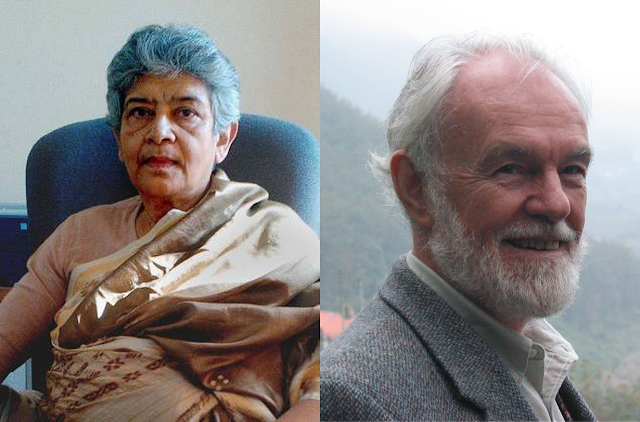

| Utsa Patnaik y David Harvey |

David Harvey has been outspoken on pointing out that we should look at the mass of profit instead of the rate of profit as part of the functioning of capitalism. I recently re-read Capital and found some support for his outlook here, on chapter 25 of Vol. I called The General Law of Capitalist Accumulation: "The reason is simply that, with the increasing productivity of labour, not only does the mass of the means of production consumed by it increase, but their value compared with their mass diminishes. Their value therefore rises absolutely, but not in proportion to their mass. The increase of the difference between constant and variable capital, is, therefore, much less than that of the difference between the mass of the means of production into which the constant, and the mass of the labour power into which the variable, capital is converted. The former difference increases with the latter, but in a smaller degree." (Marx, Capital Vol.1, Ch. 25)

I’ll begin by pointing out that this is a metatheorem, one of many Marx uses all through Capital. I don’t know many positions which remark the character of metatheorems of most of Marx’s prose texts, but they are. Besides the mathematical discussion only, this means we’re dealing with a quantitative relationship as well, even though if it isn’t numbers properly. So, just like the many metatheorems inside Capital, this is no different. Second of all, I want to point out that I’m interested not in capitalism in general, and not even on Marx’s accumulation law as a whole, but on devalorization of constant capital. And this is, I think, what connects Harvey’s preoccupation with mass, with Marx’s assertion on the law of accumulation also being made specifically on mass and it’s effects. Of course, Harvey is referring to (mostly) the fall in the profit rate debate, and (mostly) it’s effect on crises (we disagree with Harvey on calling the rate of profit monocausal, for example, since Carchedi has done a great work in dealing with multiple sufficient causes, even if the fall in the profit rate is a necessary cause, just to clear this up quickly). Something which I want to clear out I’m not talking about or at least, I’m not centering myself upon this through this simple notes. I just see how both positions are centered on mass, even though Marx includes way more concepts and empirical aspects than Harvey, and even if they have different subjects at hand. That doesn’t prevent their notions (specially Marx’s, obviously) to be useful to analyze aspects of capitalism like the one I’m talking about: the devalorization of constant capital. One could ask, devalorization of constant capital in relationship to what? Well, in relationship to this work I’ve elaborated on why East Asia and the Pacific (excluding Japan) was taking up roles classically thought to be produced only by imperialist superpowers (they’re the center of industrial and high tech production in the world, bigger exporters of capital goods, etc, just like Lenin defined it for the Triad a century ago), and how this relative inversion of roles between core and peripheries could have taken place.

This is slightly different to the ‘imperialism in the XXI century’ debate, in the sense that we’re not talking about a radical inversion between the Triad and the so called “Third World”, where the Triad gets to be poor, and the E20 is now the hegemon, or something ridiculous like that. We mean a repositioning of tectonic plates in the world market, which don’t eliminate classical features of imperialism, but at the same time, change them completely. Either way, it does give support, even in terms of the imperialism debate, to a more mixed scenario within the different positions that have been defended up until now regarding the XXI century. It even answers some of the questions people like Utsa Patnaik have raised regarding this change: how come the peripheries are now more attractive to global capitals for them to invest, and why didn’t they started to invest in the “Third World” to begin with? If the lower organic composition of the “Third World” is real, then why didn’t the Triad’s capitals flow into the “Third World” and produce the post-war boom there, instead of in the Triad, for example? Or in other words: how come production was backwards and stagnated in places like, for example, India, and then suddenly the “green revolution” appeared? How come there was such a low investment before, and then there was a qualitative leap forward in capitalist investment?, etc.

The answers developed here are of tremendous importance for the “Third World”. It could change the way their stories are told, and how history has affected their present lives. We started our initial position by, basically, formulating the fact that the lower organic composition in the peripheries, created a bigger profit rate, and this stagnated investment in order to keep the rate bigger. At the same time, this allowed for a margin or difference between the rate of profit and the rate of accumulation, to be a little bit wider than in the Triad, and so when the fall in the rate of profit started to kick in during 1973/74 (!), then it was more profitable to invest in the Third World than in the Triad, causing the industrialization of the “Third World” (taylorist and neo-fordist in Lipietz terms), and this in its turn, changing or inverting the roles of each region of the world market, and allowing for the phenomena described in my work above, basically the entering of the Asian Tigers, and the whole process of accumulation in East Asia and Pacific, and even South Asia, with imperialist Japan supporting them geopolitically, etc. But as you can see, Patnaik’s doubts are still of very much concern even within this explanation I’m giving: the margin or difference between profit rate and accumulation rate was there from the beginning, if we assume with Marx that there was a lower organic composition, and so, a bigger profit rate. Plus, the industrialization of agriculture, which is basically what the “green revolution” was, started way before the sharp decline of the profit rate in 1973/74 (although the fall in the profit rate was a process, and not a simple break, envisioned by economists all over like Mandel, etc).

So here are a few notes which might explain how come did this qualitative leap or break happened, and it turns out that it has to do with the devalorization of constant capital, just like in Harvey’s position, and just like the famous counter-tendency to the fall in the profit rate in Vol. III. So here are the notes:

- Just like devalorization of constant capital cheapens the older means of production, but at the same time, it turns them into more expensiveconstant capital in terms of productivity (that’s why they lose value and become backwards), in the same way turns more expensive the new means of production (because they’re innovations), and at the same time, makes them cheaper and less expensive in terms of productivity (which is why they’re advantageous). So we’re not like Enrique Dussel here: we don’t include devalorization only at the circulation level, like the inability to sell commodities, etc, and not only is devalorization destructive for capital, but also productive for it as devalorization itself. Devalorization and valorization are not two dialectical poles, but they’re interpenetrated. As we will show, devalorization actually helps valorization and viceversa, dialectically, but not like polarities.

- So following Marx: an increasing accumulation rate increases the mass of surplus value, which in its turn increases the rate of profit due to an increase in the productivity of labor. The profit rate falls when the accumulation rate decreases, and there’s no more increases in the mass of surplus value. So when the accumulation rate approaches the rate of profit (just like in our initial thesis) in the core-central countries, the rate of profit’s growth contracts compared to the peripheries, because the accumulation rate itself has as it’s top limit the profit rate. In the peripheries, on the other hand, the margin or difference between accumulation rate and profit rate is bigger, not because of accumulation (which is backwards), but because of the larger profit rate (precisely because it is backwards and there’s a lower organic composition).

- So the accumulation rate starts to grow slower and less than the organic composition in the core-central metropolitan countries, and this means that, comparatively and relatively, the accumulation rate starts to grow more and faster than the organic composition in the peripheries. Here now is Patnaik’s question finally answered (or at least a possibility for it), in the sense that this explains the qualitative leap itself. Just like there’s a threshold in the interplay between the profit rate and the accumulation rate for the profit rate to fall, where the profit rate falls immediately but still mainstains itself above accumulation, and so expanded reproduction can still be maintained, and the actual problem arises when the profit rate violates that threshold and goes below the accumulation rate, then the same happens with this law of accumulation: organic composition increases, but the mass of accumulation increases more, to a point where the mass of accumulation stops growing more than organic composition, and constant capital starts to get valorized, producing devalorization dialectically.

- This law of accumulation, as Marx calls it, although it looks just like a different wording for the same counter-tendency of cheaper and devalorized constant capital from vol. III, it’s actually completely different. The law of accumulation is a process of devalorization of constant capital, but it’s also an increase of the mass of surplus value based on that devalorization, and it’s also what explains the competitive devalorization of the constant capital which is not innovative, which in its turn explains the ‘foreign trade’ counter-tendency right next to the others in Vol. III (which is why is so useful to understand the world market, and this long held processes between the Triad and the so called “Third World”). The law basically includes three (maybe more?) counter-tendencies. Just like in a single economy, innovation cheapens and devalorizes the rest of constant capital which is older, making it more expensive in terms of productivity (it doesn’t produce as much as the new technologies) but still lowers its value and organic composition. This explains why the “green revolution” and the other forms of industrialization of the “Third World” happened along the lines of Lipietz’ taylorism and neo-fordism: as Lipietz’ points out, industrialization of the “Third World” was and is a reality specially since the latter half of the XX century, but this was produced mainly with backwards and cheaper constant capital. This in its turn prevented a reduction of the profit rate, which was relatively and comparatively already bigger than the Triad by definition (since it’s a lower organic composition). The Triad didn’t industrialize the “Third World” with the more advanced technology, but to the “second best”, to call it that way, the very cheapest and backwards, so it would make investment and accumulation greater, etc. But the law does even more: its not only the rest of the constant capital which gets devalorized, but the innovative constant capital itself; its not only the competition who gets its own constant capital devalorized, but the very same productive process which invests in the new constant capital. This goes way beyond the counter-tendencies of vol. III.

- This also explains the lack of investment already present in the “Third World” before the internationalization of the division of labor of late capitalism (multinational production), which precisely Patnaik pointed out. At the same time, the accumulation rate being bigger in terms of mass, explains the great advancement that the Triad had compared to the “Third World”, even if we’re talking about a catching up process or inversion of roles between the Triad and East Asia and the Pacific or South Asia, etc, it doesn’t change the fact that the Triad having the multinational world market at their disposal, and having the specific productivity of labor described by Marx in terms of mass of accumulation, offsets the fall in the profit rate, and allows them for a relative space of maneuver. At the same time, this advancement itself is its own predicament: productivity and the mass of accumulation are so big, that organic composition rises, and this makes the peripheries into comparatively and relatively better stages for international investment (which is what Marx means by ‘foreign trade’). This explains our original proposal of production based on productivity of labor or exploitation rates. Productivity contains exploitation, but exploitation rates don’t include productivity. The relationship is asymmetrical. So productivity of labor not only decreases necessary labor in relationship to surplus labor (instead of the reduction in the price of labor of exploitation rates), and not only it allows for a reduction in unitary prices while at the same time appropriating more value through those same smaller prices, etc, but it also allows for a growth of the rate of accumulation relative to organic composition, and so, a relative growth of accumulation in relationship to the profit rate. As Harvey aptly points out: if you have a 50% profit rate for 100 bucks, and a 5% profit rate for 100,000,000,000 dollars, then you’re going to prefer the latter smaller rate, because it means an absolute mass or amount or magnitude of profits which exceeds by far the larger profit rate. This explains precisely the lack of investment in the “Third World” which Patnaik has mentioned since the modes of production debate in India, and the stagnation of investment and productivity all over the “Third World” before the “green revolution”. But then, this absolute amount also diminishes it’s growth (its not negative growth, but a slower positive accumulation, just like the accumulation rate diminishes but keeps growing following the profit rate), and constant capital starts to be more expensive, increasing organic composition, and so ending the postwar boom and forcing to look for alternatives like investment in the “Third World”. It is here that the difference we remarked, between the profit rate and the rate of accumulation being wider in the “Third World” is seized as an opportunity for a more expansive and stronger expanded reproduction. And voilá, the roles get reversed.

- This is also important to be more nuanced and detailed on this processes and so being more precise: if we propose that the Triad started with production based on productivity of labor, and the “Third World” was dedicated to production based on labor exploitation, that doesn’t mean the current reversal of this situation stops the Triad from using productivity of labor, or capital-intensive policies of innovation, which still produce organic composition to rise there, and keep pushing the profit rate to new lows. Is just the predominant tendency: as we showed in our original elaborations titled Adam Smith in Beijing on our site, neoliberal policies of flexibilization, unemployment, and reduction of nominal or real wages, are all basically based on labor exploitation, and these policies have, like many Marxist economists have pointed out, helped to diminish the long fall of the profit rate (although without any serious recovery to pre-1973/74 years). But all of these has been accompanied by good ‘ol capital intensive, organic composition increasing, innovation and investment in the Triad. This also gives us a new notion: the Triad has an advantage even in these terms, and even if they explain the relative inversion of roles between the Triad and the “Third World” (or South- East Asia more specifically). Since their accumulation is more advanced, is precisely in relative terms that the mass of accumulation is bigger in the Triad than the “Third World”, not only in nation-state terms, but specially multinational: most of the new “Third World” multinationals from Africa or Central America are all regional, and not global; the Triad has at its disposal an absolute and relative bigger amount of mass of accumulation than the E20, the BRICS, the “Third World” or whatever you like. This gives strong support to the classical imperialist stance. And yet, at the same time, its completely new and not classical at all: even if the mass of accumulation is bigger in the Triad, their organic composition is also bigger, which relatively and comparatively makes it better for the “Third World” to have some space of maneuver to continue with expanded reproduction more resolutely.

- So this bigger expanded reproduction, which we investigated empirically in our texts, and which should be clear to all, is a completely new phenomenon within the world market, and at the same time, is totally “dependentist”, if you want to call it that. The industrialization of the “Third World” itself, explained by the variables we just have shown, was still produced by the Triad since the “green revolution” itself, which should be considered the first ever internationalization of the division of labor in late capitalist terms, even before any industrial sector factories or whatever multinational you like, and the first form of this “Third Worldist” industrialization at all. So industrialization started with these features, from Nehru’s India to Arab Gulf States’ oil industries, to Central American’ Costa Rican industrialization, etc, partly an opposition to colonialism, and partly a sponsored decolonization process by the colonial centers themselves (just like the Triad superpowers were actually in agreement with some aspects of decolonization, and actively supported it). Anyway, this explains the fact that this inversion of roles is still based within the asymmetry of the classical imperialist theory, but completely sustained by new forms. Forms that are changing the face of the world market and classical imperialism to the point of oblivion, as well. Even if China or India were the only superpowers to survive this upsurge all along the century, it would still be a matter of Marxists economists to explain how these two countries escaped “dependentism”, if it was supposedly ingrained and inherent in capitalism itself, like a ridiculous inverse profiting and impoverishment of North and South regions alike, etc (something as preposterous and chauvinistic as the apologetic dream of a ‘BRICS dominated future’, just to call out one example). In short, accumulation in the Triad is still more advanced, but the “Third World” is not so much catching up, as it is competing and increasing the interimperialist competition by reaching the same global arena of multinational production which the Triad had.

- This takes us to Claudio Katz’ position, and I think, Petras’ and maybe even Lipiet’z position as well, regarding the mixed character of the most recent developments in the world market, and on the imperialism in the XXI century debate specifically. Their positions are the more nuanced, concrete and historical of all, to my opinion. Mandel’s project of continuous actualization (and not simple “revisionism”) gains some hope with their works.